The Area: A Brief Water History

A Brief Water History of the San Luis Valley

The San Luis Valley is big. It extends more than 100 miles from north to south, and about 60 miles wide from east to west in southern Colorado. Around 500,000 years ago, the valley was covered by a huge lake (today known as Lake Alamosa) which was 200 feet deep in some locations. The ancient lake eventually dried up and left the expansive flat valley we see today. Lake Alamosa also deposited underground sediment layers which now hold groundwater recharged by the Rio Grande River and it’s tributaries, seepage from irrigation canals, and limited recharge from irrigated fields.

Year 1852

In 1852, the first permanent irrigation system in the region was constructed by residents of the newly established town of San Luis – an acequia called the San Luis Peoples Ditch, which today is the oldest water right in continuous use in Colorado. That same year, the US Army constructed Fort Massachusetts (later renamed Fort Garland) as more settlers arrived to settle on the fertile valley lands. In 1878 the town of Alamosa was established with the arrival of the Denver & Rio Grande Railroad. Another person to arrive was Theodore C. Henry.

Late 1800s

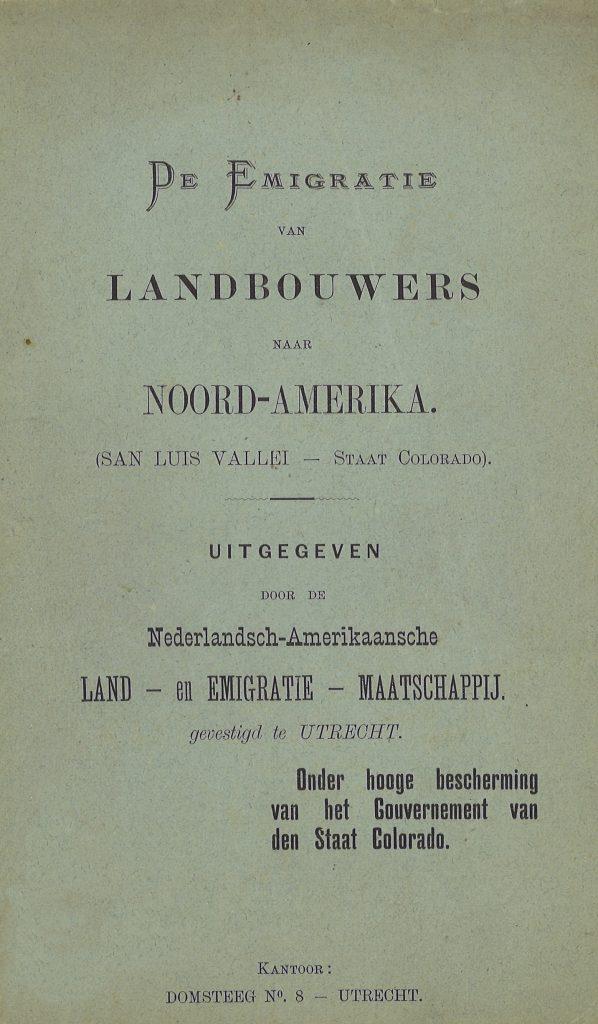

In the late 1800s, Colorado became well-known around the world for the success of its agricultural colonies, particularly the Union Colony at Greeley and the Chicago-Colorado Colony of Longmont. These settlements were well advertised and generated great interest in Europe, particularly in England and Holland. T.C. Henry was a land promoter and irrigation developer from Denver (by way of Kansas) and took full advantage of the situation.

In 1892, the Holland American Land and Immigration Company of Utrecht, Holland, (representing hundreds of potential settlers) sent an agent to the United States to select sites for new agricultural colonies. Eventually a tract of land was selected in the San Luis Valley because of available irrigation water and excellent railroad facilities – and through the prominent promotion of T.C. Henry.

The Dutch settlers made an agreement with Henry to purchase 15,000 acres under the Empire Canal near Alamosa. The immigrants arrived at Ellis Island in New York Harbor on November 26, 1892, next boarded a train in Hoboken, New Jersey, and four days later arrived in Alamosa. The economy of the Netherlands was depressed in the early 1890s, and many of these desperate farmers had spent their life savings to travel to America for a new life with their families.

Now in Colorado in late 1892, the group of 250 Dutch settlers – including adults and children – were met by a large group of people, including the mayor of Alamosa, and immediately escorted to Armory Hall in Alamosa where the townspeople prepared a lavish meal for the newcomers. Most immigrants were still in their native clothes – peaked caps and wooden shoes. Speeches were made and translated into the Dutch language. The 1,000 residents of Alamosa were happy to have these new settlers among them.

Unfortunately, tragedy struck the Dutch families almost immediately as diphtheria and scarlet fever broke out among the children, and thirteen died. Many immigrant farmers were outraged and felt deceived because their land was poor (it had been described as “the Italy of western North America”), and irrigation water was sparse. Crops withered that summer due to a lack of water and the short growing season.

The new farmers from Europe soon ran out of money and by September 1893, most Dutch settlers left for northeastern Colorado, to farms in Iowa, or back home to Holland. The only family which remained in Alamosa was that of Adolph Herrsink, who was financially able to carry on – the sole survivor of a failed experiment. T.C. Henry also left the area.

In the 1930s, tragedy struck again in the San Luis Valley. The valley’s irrigated economy had developed during the early 1900s, but national and world events now crippled the area. During the Great Depression, farm prices plummeted and the price of potatoes dropped from $4 per hundredweight in 1920 to $0.35 in 1932. Nearly 10,000 acres of cropland failed in 1934 and thousands of valley residents were forced to move elsewhere, just like the Dutch settlers 40 years earlier.

Fortunately, the rains returned, and irrigation water from the Rio Grande River lifted the local economy in the 1940s. The invention of center pivot irrigation systems in the 1950s – quarter-mile long pipes elevated on wheels that could irrigate an entire field in a day with the push of a button – changed irrigation in the valley forever. The two enormous aquifers that laid beneath the valley floor for centuries were tapped and supplied irrigation water for center pivot wells constructed during the mid-1900s and later.

Lake Alamosa

Going back to prehistoric Lake Alamosa, ancient-deposited sediments allowed groundwater to recharge and reside at varying levels beneath the land surface of the San Luis Valley. The deepest groundwater – called the confined aquifer or Closed Basin, contains groundwater at depths of around 800 feet (245 meters).

Other sediment deposits hold groundwater at lesser depths – at around 100 feet (30 meters). This layer of groundwater and sediments is called the unconfined aquifer and is replenished (recharged) from surface water in the Rio Grande River and unlined irrigation canals in the area.

This shallow aquifer supplies about 85 percent of the agricultural irrigation water in the San Luis Valley. The largest concentration of use is in the northern part of the valley near Center and Del Norte, and is the region served by Subdistrict #1 of the Rio Grande Water Conservation District.

More Recent History

In 1967, the Rio Grande Water Conservation District was formed by the Colorado General Assembly and a vote of residents within its boundaries. The district was created to “protect, enhance, and develop water resources in the Rio Grande River basin.” In 2006, Subdistrict #1 of the Rio Grande Water Conservation District was created to mitigate rapidly declining groundwater levels caused by prolonged drought and increased groundwater pumping in the area.